The Story…

Once upon a time, on the island of Rhodes, there was a brave man of the Order. This man’s name was Gozon, and he was a Frenchman from Gascony. Gozon was a man of honour and of great fortitude; he was, by all extensions of the word, a knight.

But, as we know from all of the stories and fables, every brave knight has a wicked enemy – and none were quite as wicked as Gozon’s. For, on the island of Rhodes in the fourteenth century, it is said that there dwelled a fearsome dragon. So fearsome, was this creature, that the Grand Master of the Order himself had forbade any knight from trying to slay it – because he had lost too many good men to the fruitless endeavour.

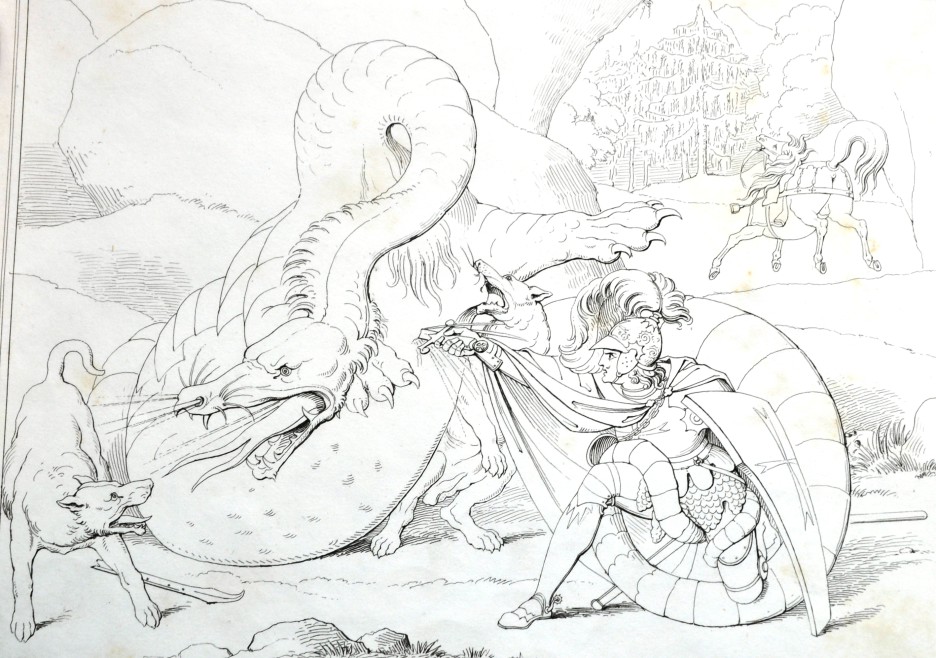

But, being the valiant man that he was, Gozon was not to be deterred by his Master’s orders. So Gozon hatched a plan. He obtained permission from the Grand Master of the Order to leave Rhodes and visit his brother in Gascony. Here he constructed a replica dragon, to the exact scale of the actual beast, to use as a training aid for his dogs and horse. He had his servants animate the dragon, moving its tail, head, legs, mouth and wings in an attempt to prepare the animals for the fight, and allow them to grow accustomed to the fearsome beast. Once the Knight was confident that his horse and dogs wouldn’t falter in the face of the monster, he returned to Rhodes to face the dragon. Gozon sent the majority of his armour to the Church of St Stephen’s, which stood on a hill overlooking the dragon’s lair. Whilst hiding the rest of his armour underneath his cloak, Gozon made his way to the dragon’s lair on horseback, with his dogs following close behind.

Gozon spurred his horse to gallop towards the mouth of the chasm, where the dragon had made its den. And, with lance in hand, he rode to face the monster. He made his way up the stream, towards the chasm’s opening, and from it emerged the dragon with a mighty roar. Gozon waited, still mounted on his horse, for the dragon to attack. The horrible monster suddenly appeared with its usual hissing and hoarse roar, and flapping his wings flew at the Knight with incredible fury! In the words of the nineteenth-century German poet / playwright / historian, Friedrich von Schiller:

“Its stretching neck appeared to swell,

And, ghastly as a gate of hell,

Its fearful jaws were open wide,

As if to seize the prey it tried;

And in its black mouth, ranged about,

Its teeth in prickly rows stood out;

Its tongue was like a sharp-edged sword,

And lightning from its small eyes poured;

A serpent’s tail of many a fold

Ended its body’s monstrous span,

And round itself with fierceness rolled,

So as to clasp both steed and man.”

Gozon lowered the visor of his helmet, drew a deep breath and spurred his horse toward the dragon, raising his lance at the beast. The lance struck the dragon, but it splintered into a thousand pieces on the beast’s thick hide. One of the dogs managed to clamp its jaws shut on the dragon, and Gozon used the distraction made by his faithful canine companions as an opportunity to dismount his horse and grab his sword and shield.

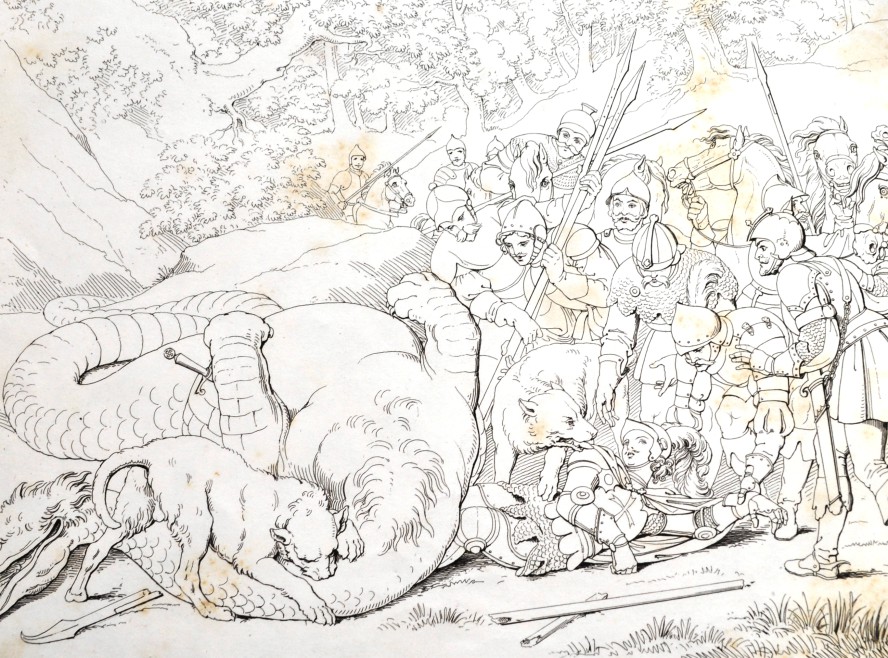

The dragon slashed at the Knight; he would have been crushed had his armour not protected him. Every form of attack was being deflected by the dragon’s scales, it was becoming increasingly apparent that Gozon might not be able to best his foe. But, from the corner of his eye, Gozon spotted a loose scale on the dragon’s underbelly. The Knight and the beast lunged for each other, the dragon pressing Gozon to the ground as he thrust his sword through the loose scale and into the dragon’s chest. The beast eventually fell lifeless on top of Gozon, where he remained pinned for some time. Feebly, once he had been freed from underneath the defeated dragon, Gozon mounted his horse and returned to the city, dragon head in hand, to tell the Grand Master of his great victory.

However, the Grand Master was not pleased, having forbidden any Knight from challenging the dragon. He had Gozon imprisoned in a tower and, eventually, brought him in front of the Council to have his Habit removed. However, after long deliberation and in consideration of his magnificent victory, the Grand Master decided to have him reinstated into the Order, restoring his Habit and seniority. “Thenceforward, Dieudonne de Gozon was so highly honoured by the Grand Master and Convent alike, that four years later he attained to the Magistracy himself”. Or, at least, that’s how the story goes.

What we know…

Gozon himself was a real man, and his full name was Dieudonne de Gozon. Just a few years after his supposed battle with the dragon, Gozon was elected Grand Master of the Order, after the death of de Villeneuve. In general, Gozon’s time as Grand Master was relatively uneventful – though he did manage to further his reputation as a brave knight after marching to the aid of the King of Armenia, who was being threatened by the army of the Sultan of Egypt, in 1348.

Sadly, however, it’s unlikely that there is much, if any, historical truth to the dragon story. Hasluck, writing in 1913, noted that the story of Dieudonne de Gozon and the dragon wasn’t current in Rhodes much before 1521 – a hundred and seventy years after its hero’s death. Although in the area of Cos, which was a possession of the Knights much like Rhodes, there was a simple legend of a dragonslaying with an anonymous hero, current as early as 1420. Later accounts, namely that of the traveller de Breves, give a slightly different version, making the gallant deed of de Gozon an attempt to rehabilitate himself after initially failing to defeat the dragon.

Historically, for the alleged representation of the combat and the words ‘Draconis Extinctor’ on the tomb of de Gozon at Rhodes our only authority is Bosio, who in all probability was never on the island, since in his time the seat of the Order had been removed to Malta. A genuine sarcophagus of de Gozon was removed from Rhodes to France in 1877, and is now in the Cluny Museum. It is very plain, but it does contain fragments of the legend. A head supposed to be that of the dragon slain by de Gozon was seen by the seventeenth century traveller, Thevenot, hung up in one of the gateways of Rhodes. However, there is no mention of this head being hung on a gate by Bosio or any earlier writer than Thdvenot. Subsequent writers speak of such a head (or heads) in a similar position; it seems to have disappeared by 1839, however. It should be noted that, like all the other tangible evidence of de Gozon’s battle with the dragon, the dragon’s head at Rhodes is first mentioned long after the death of the hero.

A final, and more plausible theory is put forward by Hasluck. All over France, and apparently also in the Netherlands and Spain, are found traces of medieval festivals, generally in connection with Rogation processions, in which dragons were an important feature. A figure of a dragon, originally symbolising the ‘Spirit of Evil’, was carried or led in procession for three days and then sometimes ‘killed’ in a sort of religious play. So, there is the possibility that when Gozon asked the Grand Master to return to France to see his brother, he may well have taken part in one of these festivals. Gozon’s exploits in France may well have traveled back to Rhodes with him, and the story might have evolved over time to become a tale of a ‘real’ dragon slaying by the time Bosio was writing.

Personally, I feel that the timing and the subject of Bosio’s story is quite important. Bosio wrote his version of the Gozon dragon slaying tale in the 1590s, twenty-five years after the Great Siege of Malta. Being born in 1544, to a noble Italian family who had a rich history with the Order, the Siege of Rhodes would have been a story that he was very familiar with. Not only that, but the Great Siege of Malta would have been a major event within his own lifetime. He was also very familiar with the deeds of Jean de Valette, the Grand Master of the Order and celebrated hero during the Great Siege of Malta, and this all could have played an important role in the re-recording of the deeds of Gozon.

The story of Gozon and the dragon could perhaps be seen as symbolic of the Siege of Malta. As Bosio’s story goes, the dragon was an enemy that could not be defeated by any other Knight, just as the Knights had failed to defeat Suleiman the Magnificent during the Siege of Rhodes in 1522. It took a brave, strong and honorable French Knight, Gozon, to defeat the dragon. Just as it took a French Knight of similar caliber, Valette, to defeat Suleiman during the siege of Malta. There are other similarities between the Great Siege and Bozio’s account, such as the fact that the battle took place on both land and water, much like battles in the Siege which took place on both land and water. It is also significant that Gozon relied heavily on the aid of his trusted dogs to weaken the dragon, before he could deal the final blow, just as Valette relied heavily on his commanders and a significant relief force to finally lift the siege. Obviously, this is all speculation, but it does prove to be an interesting comparison.

Maybe Gozon actually dispatched a large crocodile, which could have somehow found itself on the island of Rhodes. Or perhaps the story is actually just a fable, with the overall message being that one should fight their own battles, stick by their principles and face their fears. Then again, maybe Gozon actually did kill a dragon. The likelihood is that we will never know…

Still, the story was powerful enough to inspire a nineteenth-century German poet / playwright / historian, Friedrich von Schiller, to write a poem about Gozon’s exploits in 1825, and for a production company to consider using it in a documentary, in 2012. It was even so widely believed that it was noted on Gozon’s own tombstone, having been given the title ‘Extinctor Draconis’. So, in a way, whether or not this actually happened is unimportant – Gozon has still gone down in the annals of history as ‘The Dragon Slayer’.